Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease–Asian perspectives: the results of a multinational web-based survey in the 8th Asian Organization for Crohn’s and Colitis meeting

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

As the characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) differ between Asians and Westerners, it is necessary to determine adequate therapeutic strategy for Asian IBD patients. We evaluated the current treatment of IBD in Asian countries/regions using a web-based survey.

Methods

The Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal Diseases conducted a multinational web-based survey for current IBD care in Asia between September 16, 2020, and November 13, 2020.

Results

A total of 384 doctors treating IBD patients from 24 Asian countries/regions responded to the survey. Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, anti-integrins, and anti-interleukin-12/23 agents were available for use by 93.8%, 72.1%, and 70.1% of respondents in Asian countries/regions. Compared with a previous survey performed in 2014, an increased tendency for treatment with biologics, including anti-TNF agents, was observed. In the treatment of corticosteroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis, 72.1% of respondents chose anti-TNF agents, followed by tacrolimus (11.7%). In the treatment of corticosteroid-refractory Crohn’s disease, 90.4% chose anti-TNF agents, followed by thiopurines (53.1%), anti-interleukin-12/23 agents (39.3%), and anti-integrin agents (35.7%). In the treatment of Crohn’s disease patients refractory to anti-TNF agents, the most preferred strategy was to measure serum levels of anti-TNF and anti-drug antibodies (40.9%), followed by empiric dose escalation or shortening of dosing intervals (25.3%).

Conclusions

Although there were some differences, treatment strategies for patients with IBD were mostly similar among Asian doctors. Based on the therapeutic outcomes, it is necessary to identify the most appropriate therapeutic strategy for Asian IBD patients.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), has been increasing over the last three decades in newly industrialized countries as they have become more Westernized, including Asian countries such as Korea, Japan, China, and India [1-4]. In a population-based study from Hong Kong, the incidence of IBD per 100,000 individuals, increased from 0.10 in 1985 to 3.12 in 2014 [5]. A Taiwanese retrospective study using a nationwide insurance database also reported a rapid increase in the incidence of IBD since 2001. 3 In addition, a recently published Korean population-based cohort study reported that the adjusted mean annual incidence rates of CD and UC per 100,000 inhabitants increased from 0.06 and 0.29 in 1986–1990 to 2.44 and 5.82 in 2011–2015, respectively [6].

The clinical characteristics and natural history of Asian patients with IBD have been reported to differ in many aspects from those of Western patients with IBD. In Asian patients with CD, a male predominance, less prevalent isolated colonic disease phenotype, and a higher prevalence of perianal fistulas/abscesses have been reported [6-11]. In Asian patients with UC, a higher proportion of proctitis has been observed [6]. However, regarding genetic susceptibility, NOD2, a well-known CD-susceptible gene in Western patients, did not show an association with CD in Asians, whereas TNFSF15 was reported to be more strongly associated with CD in Asian patients [12,13]. Moreover, a recently published Korean study identified 3 novel susceptible loci for IBD that have not been previously associated with IBD in Western populations [14].

To date, most of the widely accepted guidelines for the management of IBD have been published based on studies conducted mainly on patients with IBD in Western society [15-21]. Although some Asian countries have developed their own guidelines tailored to the situation of each country [22-26], there could be regional differences in the therapeutic strategies for IBD patients according to countries. Hence, in 2014, a web-based multinational survey on the current IBD treatments performed by medical doctors who treat IBD patients in Asian countries was conducted at the second annual meeting of the Asian Organization for Crohn’s and Colitis (AOCC) [27]. However, since 2014, advances in therapies, including newly developed biologics and small molecules, have emerged for IBD management, and many Asian countries have become more industrialized; thus, there is a need for an updated survey on the current status of IBD therapies in Asia.

Considering the above, the Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal Diseases (KASID) conducted an online survey on the current status of IBD therapy. Here, we evaluated the current treatment of IBD in Asian countries/regions based on data from a web-based multinational survey of medical doctors treating patients with IBD.

METHODS

1. Survey

The first survey on Asian doctors’ perspectives regarding the management of IBD was conducted in 2014 as one of the programs of the second annual meeting of the AOCC [27-29]. For follow-up research, a second survey was conducted by the KASID, and the results were presented at the 8th annual meeting of the AOCC, which was held as a virtual congress in December 2020. The questionnaire for this research was developed in collaboration with the International Academic Exchange Committee, Scientific Committee, and IBD Research Group of the KASID. A web-based survey with 95 questions was sent to approximately 16,000 multinational AOCC members with available email addresses using SurveyMonkey® (https://surveymonkey.com/). Responses were collected online between September 16, 2020, and November 13, 2020. Because this study did not include any animal or human data and only report the results of web-based survey as in previous AOCC survey, ethical approval and informed consent to participants were not applicable.

The survey mainly consisted of 5 parts: personal information (8 items), diagnosis of IBD (17 items), treatment of IBD (33 items), infections in IBD patients (22 items), and vaccinations in IBD patients (15 items). Details of the questionnaire are provided in the Supplementary Material. In regard to the treatment of IBD, the questionnaire consisted of the following subjects: currently available treatments in each country/region, the treatment strategy for UC, treatment of acute severe UC, treatment of corticosteroid-refractory and corticosteroid-dependent UC, treatment strategy for CD, treatment of mild to moderate CD, treatment of moderate to severe CD, treatment of refractory CD, maintenance treatment for CD, and treatment of postoperative CD.

As in the previous AOCC survey performed in 2014, small bowel CD was defined as CD involving the small bowel with or without colonic involvement (Montreal classification L1 or L3), while colonic CD was defined as CD involving the colon without small bowel involvement (Montreal classification L2) [27,30].

2. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages and analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. General Information about the Survey Participants

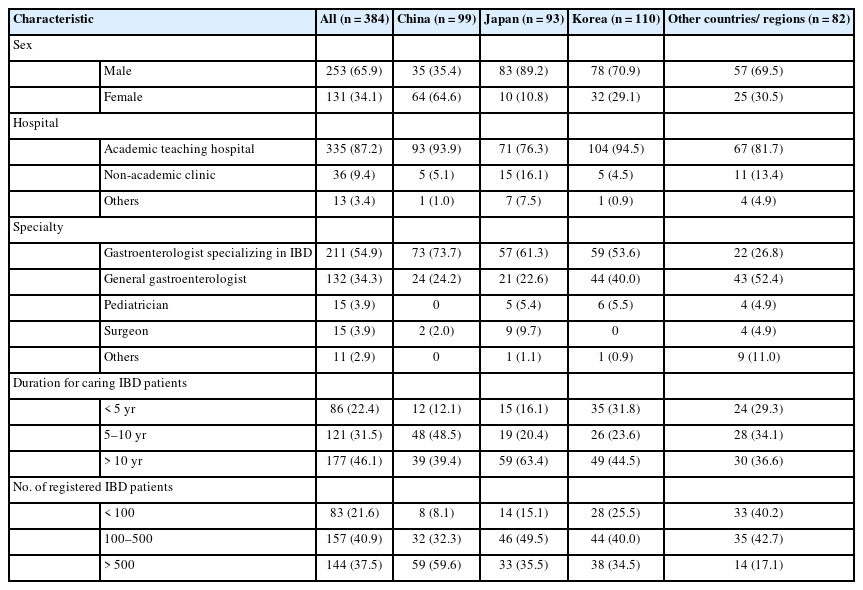

A total of 384 doctors from 24 countries/regions participated in the survey. The countries/regions of the respondents were as follows: Korea 110, China 99, Japan 93, Taiwan 20, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China 10, Vietnam 8, Indonesia 7, Malaysia 6, India 6, Philippines 4, Pakistan 3, Australia 2, Bangladesh 2, Myanmar 2, Thailand 2, Turkey 2, Egypt 1, Iraq 1, Lebanon 1, Mongolia 1, New Zealand 1, Singapore 1, United Arab Emirates 1, and Uzbekistan 1. Of these respondents, 65.9% (253 of 384) were male, and most of them (87.2%, 335 of 384) were working in academic teaching hospitals (Table 1). Among the respondents, 54.9% (211 of 384) were gastroenterologists specializing in IBD, 34.4% (132 of 384) were general gastroenterologists, 3.9% (15 of 384) were pediatricians, and 3.9% (15 of 384) were surgeons. About half of the respondents (46.1%, 177 of 384) had more than 10 years of clinical experience of caring for patients with IBD, and 40.9% (157 of 384) were managing between 100 and 500 IBD patients in their clinics (Table 1).

2. Available Medications and Treatment Strategies in IBD Patients

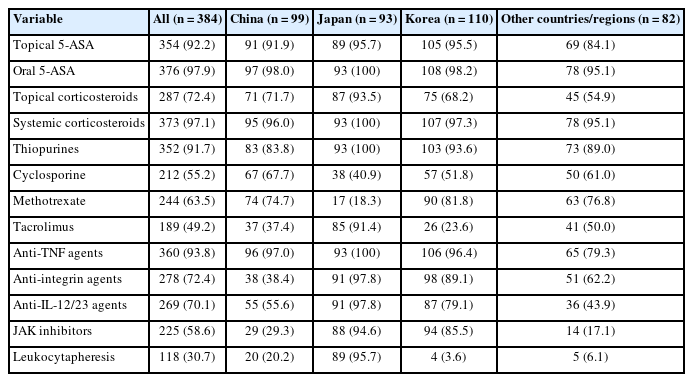

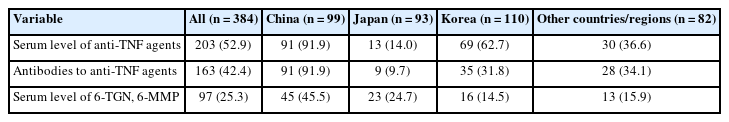

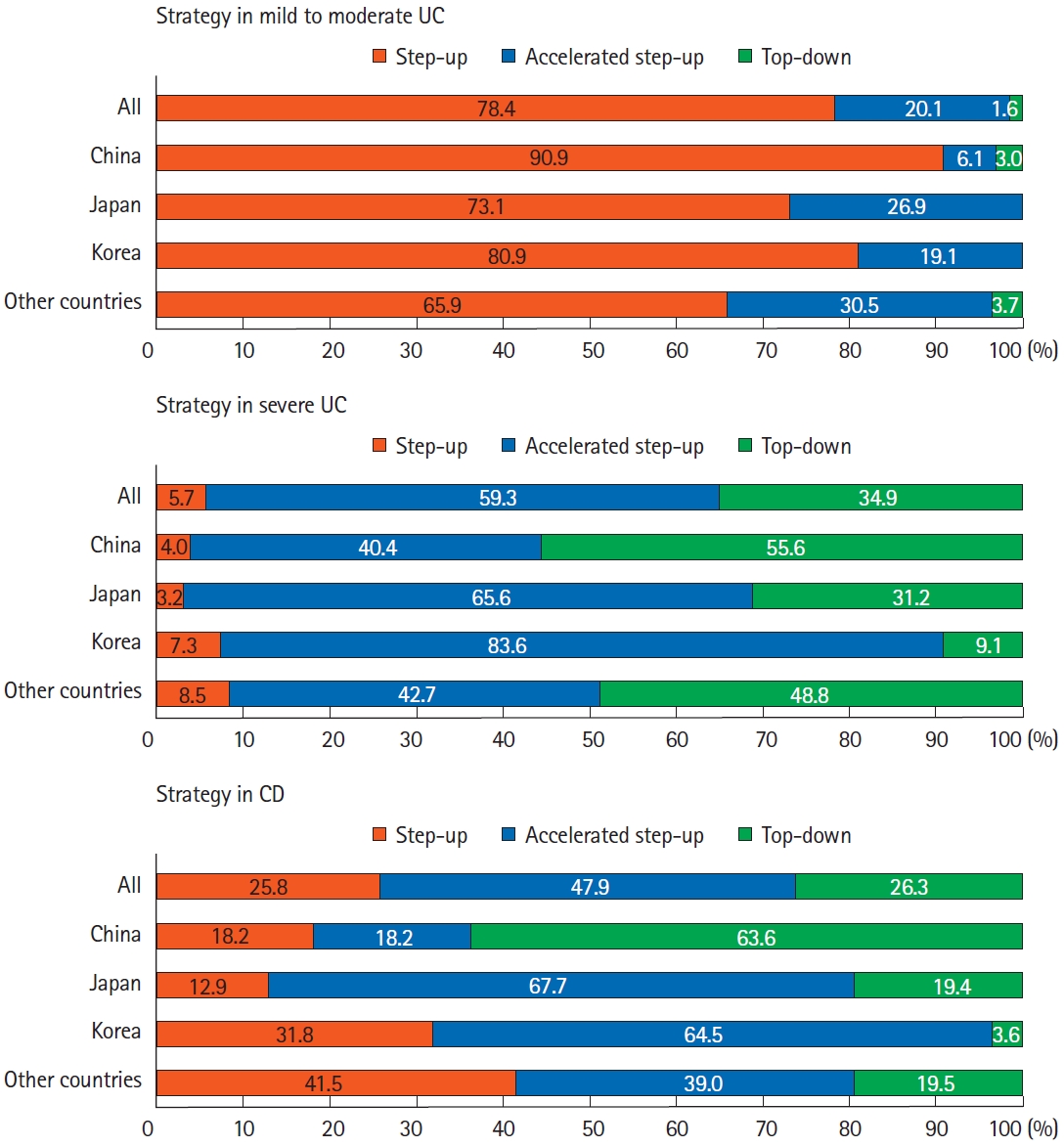

We evaluated the medications currently available for treating IBD in each county. Over 90% of respondents (93.8%, 360 of 384) replied that anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents were available in their clinical practice. In addition, anti-integrin agents, anti-interleukin (IL)-12/23 agents, and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor were available to 72.4%, 70.1%, and 58.6% of participating respondents, respectively, although there were some differences between countries/regions (Table 2). For mild to moderate UC, the step-up strategy was preferred (78.4%). However, accelerated step-up and top-down strategies were preferred for patients with severe UC. Among patients with CD, 26.3% chose top-down therapies, and 47.9% chose accelerated step-up therapies (Fig. 1).

Treatment strategy in Asian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Analysis of answers to the following questions: “Which strategy will be chosen for mild to moderate UC?,” “Which strategy will be chosen for severe UC?,” and “Which strategy will be chosen for CD?” UC, ulcerative colitis; CD, Crohn’s disease.

3. Treatment of Patients with UC

1) Treatment of Mild to Moderate UC

For the treatment of mild to moderate UC, in accordance with increases in disease extent, systemic corticosteroids were preferred more frequently (17.7% for proctitis, 26.8% for left-sided colitis, and 64.1% for pancolitis, respectively). When compared by country/region, the use of topical corticosteroids was more preferred in Japan (proctitis, 62.4% in Japan vs. 32.0% in other Asian countries/regions except for Japan, P<0.001; left-sided colitis, 67.7% in Japan vs. 33.7% in other Asian countries/regions except for Japan, P<0.001, respectively). In addition, systemic corticosteroids were more restrictively used by Korean doctors than by doctors from other Asian countries/regions (proctitis, 3.6% in Korea vs. 23.4% in other Asian countries/regions except for Korea, P<0.001; left-sided colitis, 17.3% in Korea vs. 30.7% in other Asian countries/regions except for Korea, P=0.007; pancolitis, 48.2% in Korea vs. 70.4% in other Asian countries/regions except for Korea, P<0.001).

2) Treatment of Acute Severe UC

At the initiation of treatment in patients with acute severe UC, Asian doctors reported that they always (18.5%), usually (20.8%), or sometimes (31.0%) consulted a surgeon. Korean doctors consulted surgeons more restrictively than doctors from other countries/regions. The proportion of doctors who responded that they always (90%–100%) or usually (80%–90%) consulted surgeons at the initiation of treatment for patients with acute severe UC was 19.1% in Korea compared to 47.4% in other Asian countries/regions (P<0.001). Patients’ responses to induction therapy with intravenous corticosteroids were assessed after 3 to 5 days in 68% and after 6 to 9 days in 23.4% after treatment initiation. However, there were significant differences between Asian countries/regions regarding this question; in which the proportion of doctors who chose 3 to 5 days was lower in Korea, and the proportion of doctors who chose 6 to 9 days was higher in Korea than in other Asian countries/regions (50.0% vs. 75.2% and 33.6% vs. 19.3%, respectively; P<0.001).

As the rescue therapy for patients with acute severe UC who failed to improve after intravenous corticosteroid induction therapy, 72.1% of respondents chose anti-TNF agents, followed by tacrolimus (11.7%) (Fig. 2). Approximately 4.7% of respondents chose cyclosporine as the rescue therapy for patients with corticosteroid-refractory acute severe UC. Japanese doctors preferred tacrolimus and anti-TNF agents equally as the rescue therapy: 47.2% chose anti-TNF agents, and 46.2% chose tacrolimus. When compared with the previous AOCC survey performed in 2014 [27], an increased preference for anti-TNF agents were observed: 55.8% in the previous AOCC survey versus 72.1% in the current AOCC survey.

Second-line therapy in patients with corticosteroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis (UC). Analysis of answers to the question, “Which of the followings would you consider as second-line therapy for acute severe UC patients who fail to improve on intravenous corticosteroids?” JAK, Janus kinase.

3) Treatment of Corticosteroid-Refractory and Corticosteroid-Dependent UC

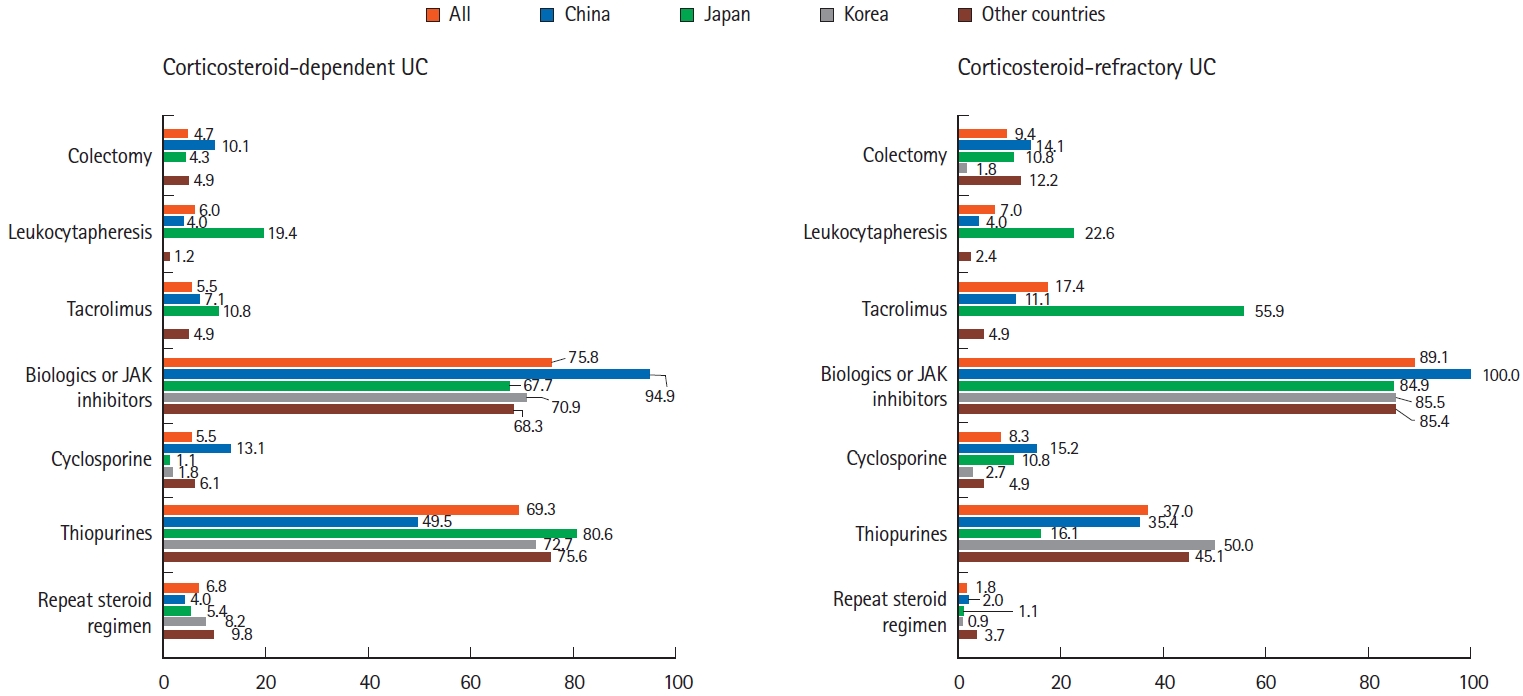

For the treatment of patients with corticosteroid-dependent UC, biologics (75.8%) and thiopurines (69.3%) were the 2 most preferred therapeutic agents (Fig. 3). Treatment with thiopurines was slightly more preferred than biologics in Japan (67.7% biologics vs. 80.6% thiopurines). However, treatment with biologics was much more preferred than thiopurines in China (94.9% biologics vs. 49.5% thiopurines).

Treatment of corticosteroid-dependent and corticosteroid-refractory ulcerative colitis (UC). Analysis of answers to the following questions: “Which of the followings would be your first choice for corticosteroid-dependent UC? (multiple choices)” and “Which of the followings would be your first choice for corticosteroid-refractory UC? (multiple choices)” JAK, Janus kinase.

In the treatment of patients with corticosteroid-refractory UC, 89.1% of respondents chose biologics/JAK inhibitors (Fig. 3). Among these biologics/JAK inhibitors, anti-TNF agents were the most preferred drugs (86.2%), followed by anti-integrin agents (40.4%), JAK inhibitor (25.8%), and anti-IL-12/23 agents (18.8%). Notably, among Japanese respondents, 55.9% preferred tacrolimus, and 22.6% preferred leukocytapheresis for the treatment of corticosteroid-refractory UC.

4. Treatment of Patients with CD

1) Treatment of CD According to Disease Location and Disease Activity

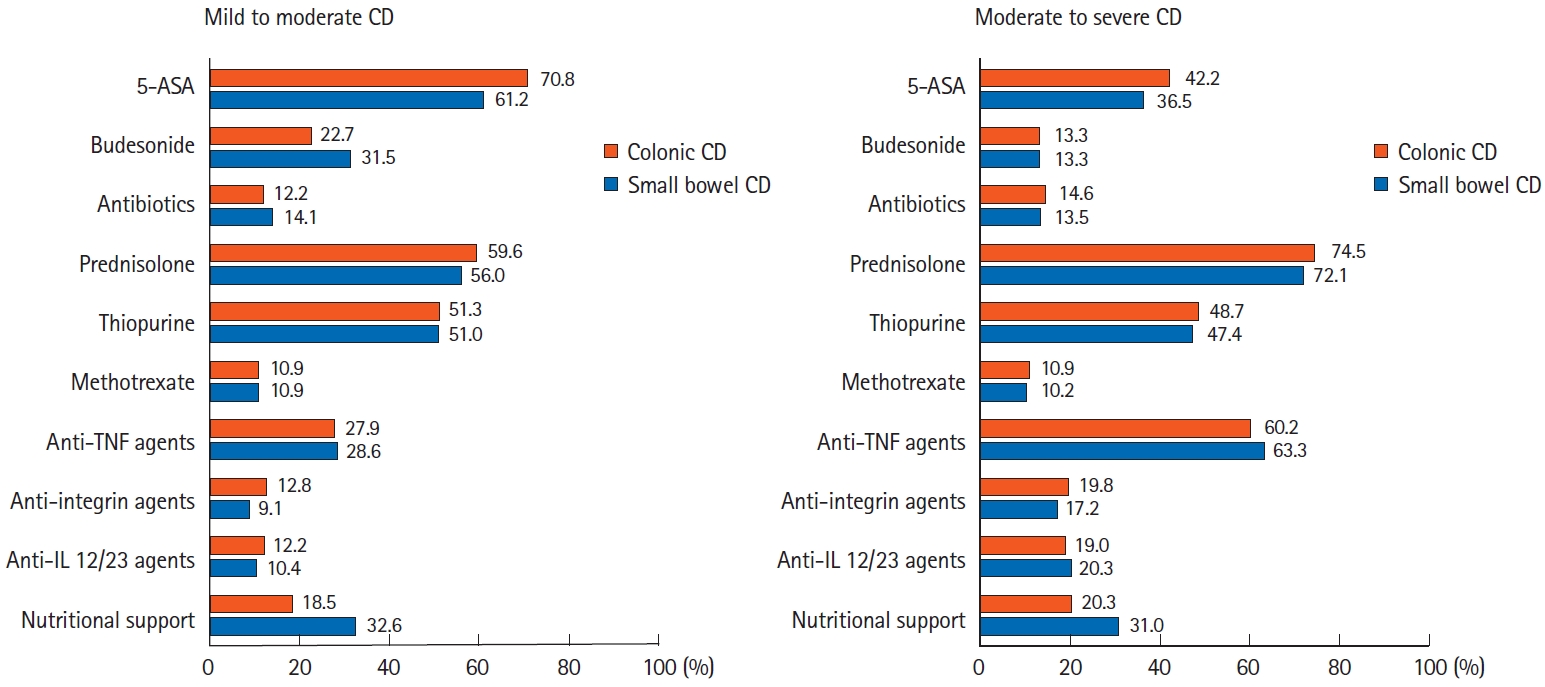

For the first induction treatment of mild to moderate CD, treatment with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), systemic corticosteroids, and thiopurines was preferred (Fig. 4). There were no significant differences in the preferred medications according to CD disease location. However, the survey data showed that 5-ASA and systemic corticosteroids tended to be more frequently used in colonic CD cases than in small bowel CD cases (5-ASA: 61.2% in small bowel CD cases vs. 70.8% in colonic CD cases; systemic corticosteroids: 56.0% in small bowel CD cases vs. 59.6% in colonic CD cases), whereas the opposite was reported for nutritional therapy (32.6% in small bowel CD cases vs. 18.5% in colonic CD cases).

Treatment of Crohn’s disease (CD) according to disease location and disease activity. Analysis of answers to the following questions: “Which of the followings would you use for the first induction therapy in mild to moderate inflammatory small bowel CD (with or without colonic involvement)?,” “Which of the followings would you use for the first induction therapy in mild to moderate inflammatory colonic CD (without small bowel involvement)?,” “Which of the followings would you use for the first induction therapy in moderate to severe inflammatory small bowel CD (with or without colonic involvement)?,” and “Which of the followings would you use for the first induction therapy in moderate to severe inflammatory colonic CD (without small bowel involvement)?” 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin.

For the first induction treatment of moderate to severe CD, although treatment based on systemic corticosteroids was the most preferred therapy, the proportion of respondents who chose biologics, including anti-TNF agents, was higher than that for mild to moderate CD (Fig. 4). There were no significant differences according to disease location. For the first induction therapy of moderate to severe small bowel CD, Korean respondents preferred treatment using systemic corticosteroids along with thiopurines and/or 5-ASA (70.9% in Korea vs. 35.5% in Japan, 26.3% in China, and 54.3% in other countries/regions, P<0.001). However, Chinese and Japanese respondents preferred treatment with biologics only (21.5% in Japan and 30.3% in China vs. 1.8% in Korea and 1.2% in other countries/regions, P<0.001). This trend was similarly observed for patients with moderate to severe colonic CD.

2) Treatment of Patients with Refractory CD

In the treatment of corticosteroid-dependent CD, anti-TNF agents were the most preferred medications (78.4%), followed by thiopurines (68.5%), anti-IL-12/23 agents (33.3%), and antiintegrin agents (31.0%). Thiopurines were the preferred medications in Korea and Japan for the treatment of corticosteroid-dependent CD. However, anti-TNF agents were the preferred medications in China. For the treatment of corticosteroid-refractory CD, anti-TNF agents were also the most preferred drugs (90.4% of respondents), followed by thiopurines (53.1%), anti-IL-12/23 agents (39.3%), and anti-integrin agents (35.7%). There were no significant differences in the preferred medications between countries/regions. Regarding thiopurine-refractory or -intolerant CD, anti-TNF agents were the most preferred drugs (69.8% of respondents). Following anti-TNF agents, a slight preference trend toward anti-IL-12/23 agents compared with anti-integrin agents was observed (14.6% vs. 6.3%).

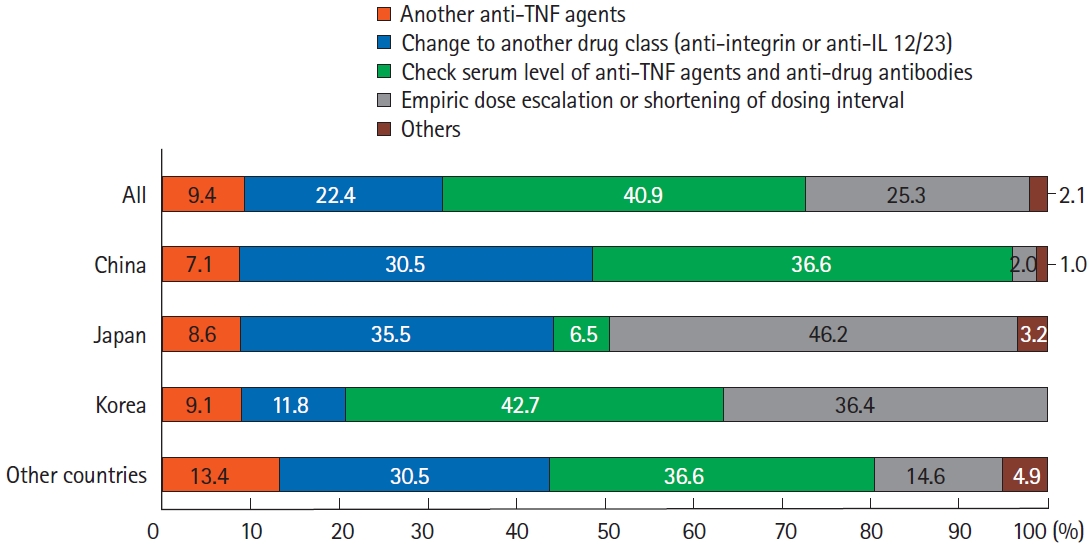

In terms of treatment strategies for non-responders to anti-TNF agents, the most preferred strategy was to check the patients’ serum levels of anti-TNF agents and anti-drug antibodies, followed by empiric dose escalation or shortening of the patients’ dosing intervals (Fig. 5). Swapping to other drug classes, including anti-integrins and anti-IL-12/23 agents, was the third-preferred strategy. Notably, there were some differences between countries/regions. In China and Korea, checking anti-TNF and anti-drug antibody levels was the preferred strategy. However, empirical dose escalation or shortening of the dosing interval was favored in Japan. Regarding therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), checking the serum levels of anti-TNF agents was restrictively used in Japan (Table 3).

Treatment of non-responders to anti-TNF agents in patients with Crohn’s disease. Analysis of answers to the question, “How would you treat non-responders to anti-TNF therapy?” TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin.

3) Maintenance Therapy and Disease Monitoring

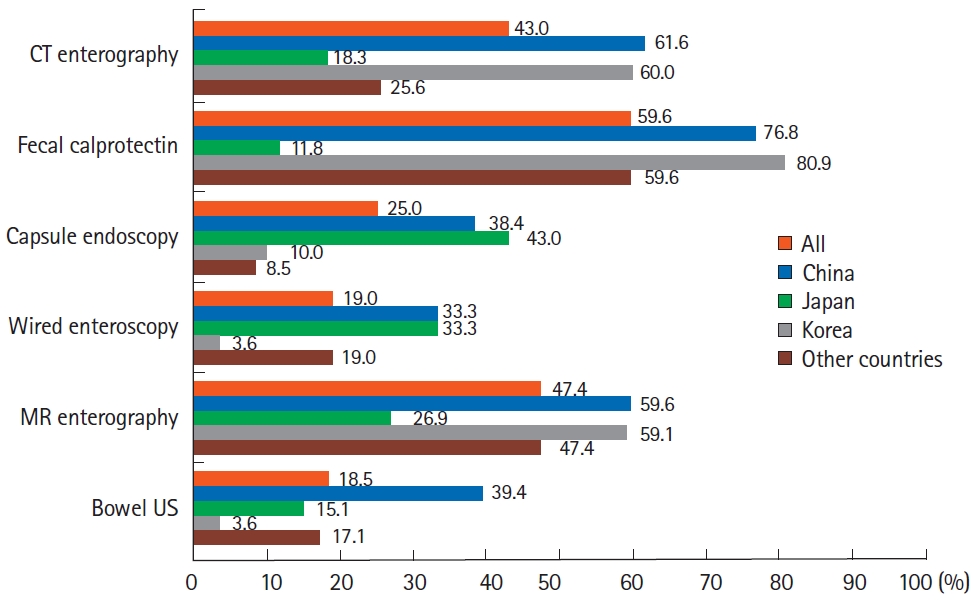

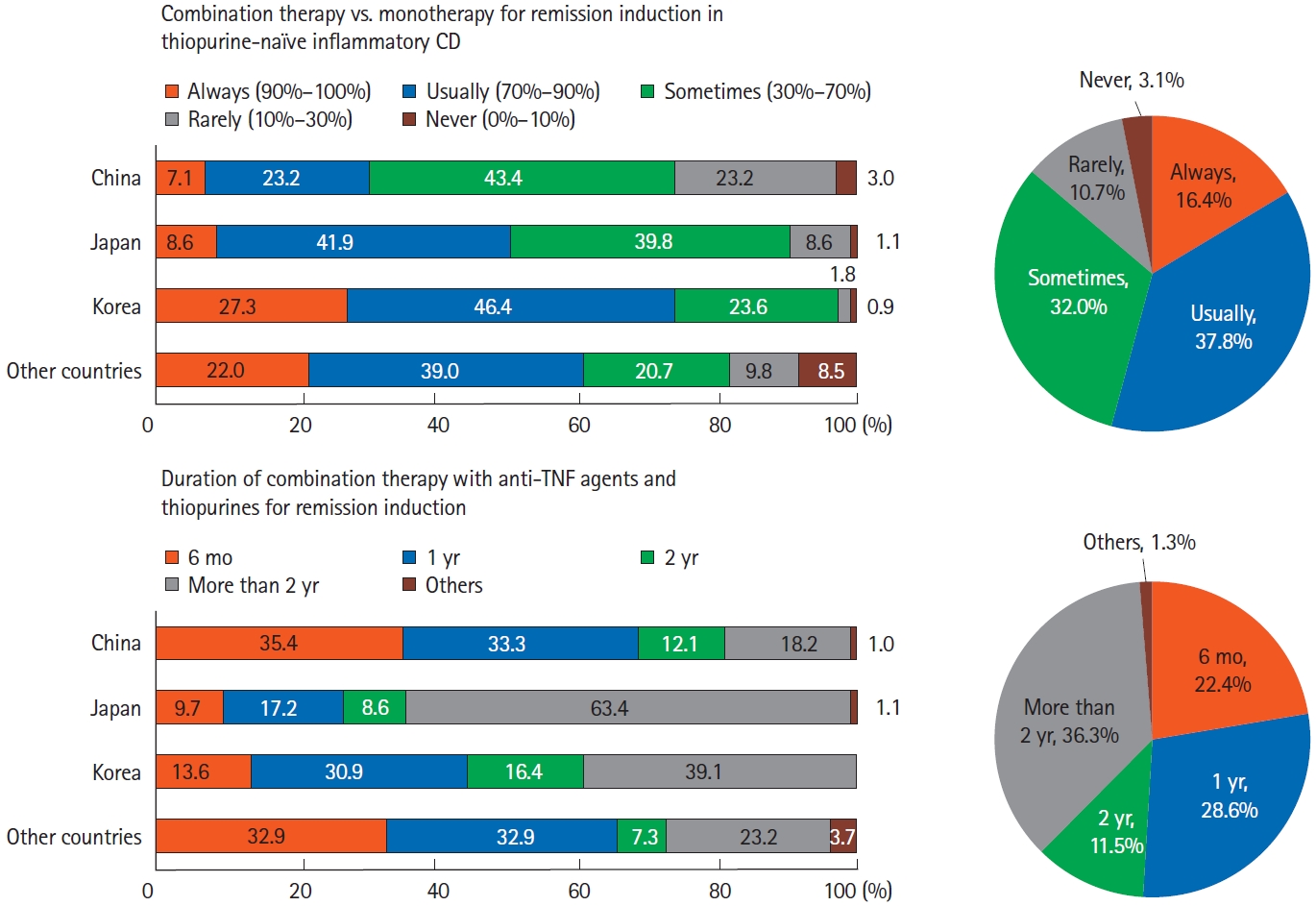

Regarding induction of remission using anti-TNF agents for patients with CD, most respondents preferred combination therapy with thiopurines over monotherapy: 16.4% of respondents always preferred combination therapy and 37.8% usually preferred combination therapy. In particular, Korean respondents preferred combination therapy (Fig. 6). Regarding the duration of combination therapy after induction therapy, 36.2% of Asian doctors tended to continue combination therapy for > 2 years. In particular, Japanese doctors strongly preferred to continue combination therapy for more than 2 years (Fig. 6). To monitor disease activity during maintenance therapy, besides conventional tools, including blood tests and colonoscopy, fecal calprotectin (59.6%), magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) (47.4%), and computed tomography enterography (CTE) (43.0%) were used in Asian countries/regions. When comparing between countries/regions, doctors in Korea and China favored CTE, MRE, and fecal calprotectin tests, whereas Japanese doctors favored direct visualization of the intestinal mucosa, such as capsule endoscopy or wired enteroscopy, over CTE (Fig. 7).

Combination therapy of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD). Analysis of answers to the following questions: “How often do you use thiopurines in combination with anti-TNF agents rather than anti-TNF monotherapy for induction of remission in thiopurine-naïve inflammatory CD?” and “How long would you use combination therapy with anti-TNF agents and thiopurines for induction of remission?”

4) Treatment of Postoperative CD

Regarding postoperative recurrence in CD patients who had been previously treated with thiopurines, approximately 90% of Asian doctors favored anti-TNF agents. For the treatment of postoperative recurrent CD patients who were treated with anti-TNF agents, the most preferred treatment was dose escalation or shortening of their anti-TNF agent dosing interval (50.5%). The second most preferred treatment strategy was to swap to anti-IL-12/23 agents (44.0%). This was followed by swapping to anti-integrin agents (35.4%), the addition of thiopurines to anti-TNF agents (34.6%), and maintaining anti-TNF agents (switching to another anti-TNF agent or maintaining previously used anti-TNF agent, 17.4%). There were no significant differences between countries/regions.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we performed a web-based multinational survey of medical doctors regarding current IBD treatment strategies in Asian countries/regions. Overall, respondents from each Asian country/region implemented similar treatments for patients with IBD and the overall treatment was not different from the recommendations in Western guidelines [15-21]. However, some differences were observed in terms of detailed aspects, such as the preferred treatment strategy, available medications, and disease monitoring tools, when compared with treatments in Western countries and compared between Asian countries/regions. For example, therapies that are not commonly used in Western countries, such as treatment with tacrolimus for patients with acute severe UC and leukocytapheresis for patients with corticosteroid-refractory UC are being currently used by Asian doctors. Of note, compared with the previous AOCC survey performed in 2014, an increased use of biologics, including anti-TNF agents, was observed in the present survey [27]. Among respondents, more than 90% responded that anti-TNF agents were available for the treatment of IBD. In addition, although there were some differences between countries/regions, more than 50% responded that anti-integrin agents, anti-IL-12/23 agents, and JAK inhibitors were available for patients with IBD.

Regarding the treatment of mild to moderate UC, the treatment strategies did not significantly differ between countries/regions: most participants chose treatments based on oral and topical 5-ASA administration, while systemic corticosteroids were preferred for patients with more extensive colitis. For treating severe UC, as previously mentioned, the use of biologics increased in the current AOCC survey compared to the previous survey. The increased use of biologics in IBD patients in Asian countries/regions was comparable to that observed in previous studies from Western countries. Targownik et al. [31] reported that the use of anti-TNF agents in a Manitoba cohort of Canada was significantly increased among IBD patients diagnosed between 2009 and 2013 than in those diagnosed between 2001 and 2005 (P=0.0048). Brunet et al. [32] also reported that the rate of treatment with biologics increased from 15.0% in 2011 to 18.7% in 2017 (P<0.001) among CD patients in Spain. In the current study, treatment with biologics or JAK inhibitors was the most preferred medication as the second-line therapy for acute severe UC: 82.8% in China, 47.2% in Japan, 89.1% in Korea, and 76.8% in other countries/regions responded that they chose biologics or JAK inhibitors. Compared with the previous AOCC survey performed in 2014 (in which 52.6% in China, 18.2% in Japan, 87.9% in Korea, and 54.3% in other countries/regions chose biologics), many more respondents preferred biologics in the new survey [27]. Considering that Asian patients with IBD have similar favorable treatment response to biologics as Westerners, use of biologics will increase further if the availability of these drugs improves in several Asian countries [33]. Interestingly, tacrolimus and biologics were preferred by 64.8% and 18.1% of Japanese respondents in the 2014 survey, whereas 46.2% and 47.2% preferred those in the current survey [27]. Although cyclosporine was reported to be as effective as infliximab in treating corticosteroid-refractory acute severe UC [34-36], only 5.0% of respondents chose cyclosporine. Overall, for treating corticosteroid-refractory UC, 89.1% of participants preferred biologics/JAK inhibitors, which is a higher proportion than that in the 2014 AOCC survey (44%) [27]. Among biologics/JAK inhibitors, anti-TNF agents (86.2%) were the most preferred agents, followed by anti-integrin agents (40.4%), JAK inhibitors (25.8%), and anti-IL-12/23 agents (18.8%), respectively.

Interestingly, there were some differences in treating patients with acute severe UC between Asian doctors. First, Korean doctors consulted surgeons more restrictively than doctors from other countries/regions. Although the reason for this result is not clear, cultural differences between Asian countries may contribute to this difference. One possible explanation for this difference is that the Confucianism, the basis of traditional Korean culture, might have made Korean patients reluctant to undergo colectomy. This might have affected Korean doctors to delay or avoid consulting surgeons as much as possible. In addition, there was a trend that some Korean doctors used systemic corticosteroids longer until the decision of corticosteroid-refractoriness: the proportion of doctors who used systemic corticosteroids for 6 to 9 days was higher in Korea than in other Asian countries/regions (33.6% vs. 19.3%, P<0.01). This might have come from some differences in treatment policies and guidelines between Asian countries. In Korean guidelines for managing UC, it is recommended to observe the response to systemic corticosteroids for 7 to 14 days before initiating other treatments in patients with moderate to severe UC. 36 Guidelines of other countries recommend a rather shorter period before initiating rescue therapy: 7 days in Japan versus 7 to 10 days in China [37,38]. The aforementioned reluctance to undergo colectomy might have also influenced on this result.

With regard to the treatment of patients with CD, anti-TNF agents were more frequently chosen for patients with moderate to severe CD (60.2% in colonic CD cases and 63.3% in small bowel CD cases) than for those with mild to moderate CD (27.9% in colonic CD cases and 28.6% in small bowel CD cases), with no significant differences between countries/regions. In addition, the preferred drugs were not significantly different according to disease location (small bowel CD vs. colonic CD) in both mild to moderate and moderate to severe CD patients. Interestingly, approximately 40% of mild to moderate CD patients and about 65% of moderate to severe CD patients were treated with oral 5-ASA, regardless of their disease location. A recent review on isolated colonic CD showed that 5-ASA was not beneficial in treating isolated colonic CD [39], whereas 2 studies published before 1990 showed a possible benefit of sulfasalazine for inducing remission of colonic CD [40,41]. However, the effectiveness of 5-ASA has not been confirmed in patients with small bowel CD [16]. Based on these results, the recently published American College of Gastroenterology guidelines and the British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines do not routinely recommend the use of 5-ASA as a remission induction and maintenance treatment for CD [16,21]. The American Gastroenterology Association guidelines published in 2021 also did not recommend the use of 5-ASA for moderate to severe luminal CD, as the efficacy of mesalamine as an induction and maintenance therapy remains unclear [20]. Regardless of these recommendations, a recently published US study using claims database reported that 37.3% of patients with CD still received 5-ASA prescription; however, the prescription rate significantly declined from 2009 to 2014 [42]. Our results also suggest that a substantial proportion of Asian doctors still adhere to the traditional use of 5-ASA, despite the increasing emergence of more potent drugs such as biologics, and may represent a knowledge gap between evidence and clinical practice.

Treatment of patients who do not respond to anti-TNF agents is challenging for physicians. In the present study, we evaluated the treatment strategies of clinicians for non-responders to anti-TNF agents. In this situation, the most preferred strategy was to check the patients’ serum levels of anti-TNF agents and anti-drug antibodies (40.9%). Compared with a previous questionnaire-based study published in 2014 that reported that dose escalation was the preferred strategy for Asian patients with initial loss of response to anti-TNF agents [43], anti-TNF TDM appears to be the preferred trend for the treatment of Asian patients with IBD. However, in Japan, only 6.5% of respondents preferred to check anti-TNF levels, and empiric dose escalation or shortening of drug intervals were the most preferred strategies (46.2%). This disparity is likely due to differences in the availability of TDM of anti-TNF agents in each country/region. Over 90% of the Chinese clinicians responded that checking serum levels of anti-TNF agents and anti-drug antibodies was an option in their practice, whereas the corresponding proportion was approximately 32% in Korea and less than 15% in Japan. Considering that reactive TDM of anti-TNF agents was recently adopted as a treatment strategy [21,23,44-47], there seems to be heterogeneity in the availability of anti-TNF TDM as a therapeutic strategy. As treatment strategies differ between countries/regions, it will be helpful to determine the most suitable therapeutic sequence for Asian IBD patients with anti-TNF-failure by comparing therapeutic outcomes.

The widespread use of imaging modalities and fecal calprotectin for monitoring disease activity during the treatment of CD is intriguing. In the previous AOCC survey performed in 2014, clinical disease activity index assessment, colonoscopy, and blood tests were the preferred methods for disease activity monitoring, and only 11% and 6% of respondents used CTE and MRE, respectively [27]. In the present survey, although clinical disease activity index assessment, colonoscopy, and blood tests were still preferred (each modality was selected by 85.4%, 83.6%, and 81.8% of respondents, respectively), the use of CTE and MRE increased to 43.0% and 47.4%, respectively. In addition, fecal calprotectin was preferred by 59.6% of respondents. In particular, the increased use of MRE was prominent, and this result suggests that more Asian doctors are now aware of the clinical significance of monitoring transmural disease activity in patients with CD with less exposure to radiation. Additionally, there was a difference in the use of disease monitoring tools in CD patients between Japan and other Asian countries/regions: Japanese doctors used fecal calprotectin (11.8%) more restrictively, whereas favoring capsule endoscopy (43.0%) and wired enteroscopy (33.3%). These results are likely due to differences in the medical environments of each Asian country/region (e.g., the use of fecal calprotectin was not approved for Japanese patients with CD when this survey was conducted).

Lastly, for treatment of postoperative CD patients with moderate to severe endoscopic recurrence who have been treated with an anti-TNF agent, the most preferred strategy was dose escalation or shortening interval of patient’s anti-TNF agent (50.5%), followed by switching to anti-IL-12/23 agents (44.0%), switching to anti-integrin agents (35.4%), and employing combination therapy with thiopurines (34.6%). Compared to the previous AOCC survey, where the respondents equally preferred the addition of thiopurines, dose escalation, or interval shortening of anti-TNF agents, the current survey results showed more diverse responses. This variation could be due to the introduction of novel biologics with new mechanisms of action [27]. It will be necessary to evaluate whether these changes in therapeutic strategies for CD patients with postoperative endoscopic recurrence will lead to better outcomes.

This study had several limitations. First, although doctors from 24 Asian countries/regions participated in this survey, approximately 80% of respondents were from China, Japan, or Korea. Therefore, our results may be biased towards East Asian countries/regions. Second, because most of respondents (87.2%, 335 of 384) were working in academic teaching hospitals, our results could be partially different with IBD treatment patterns of primary or secondary level centers. Third, we could not include or adjust for the heterogeneous health care system and services of each Asian country/region. Fourth, although we presented the overall treatment situation in Asian countries/regions, the detailed differences between our results with those from Western countries/regions could not be evaluated as this survey was conducted on Asian doctors only.

However, our study has some strengths, as it is the latest study reflecting real-life treatment situations conducted among a large number of doctors from over 20 Asian countries/regions. We also incorporated questions regarding medications available in each country/region. In addition, our study attempted to evaluate the temporal trends in the treatment of IBD in Asian countries/regions by repeating similar questionnaires asked in the previous AOCC survey performed in 2014 [27].

In conclusion, the present survey of 384 Asian doctors demonstrated that the treatment strategies for IBD in Asian countries/regions were generally comparable. However, some differences were observed in the detailed management strategies between countries/regions. In addition, compared with the previous survey performed in 2014 [27], a trend of increased use of drugs with higher efficacies, such as biologics, and more objective disease monitoring tools, including fecal calprotectin, CTE, and MRE, was identified. Therefore, it is necessary to establish the most suitable therapeutic strategy for Asian patients with IBD while considering Asia-specific medical circumstances.

Notes

Funding Source

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

Ng SC has served as a speaker for Janssen, Abbvie, Takeda, Ferring, Tillotts, Menarini, Pfizer and has received research grants from Olympus, Ferring, Janssen and Abbvie. She is scientific cofounder of GenieBiome Limited and sits on the Board of Directors of GenieBiome Ltd. Hisamatsu T has performed joint research with Alfresa Pharma Co., Ltd., and EA Pharma Co., Ltd., received grant support from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, EA Pharma Co., Ltd., AbbVie GK, JIMRO Co., Ltd., Zeria Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Daiichi-Sankyo, Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Nippon Kayaku Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Pfizer Inc., and Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and received consulting and lecture fees from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, AbbVie GK, Celgene K.K., EA Pharma Co., Ltd., Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., JIMRO Co., Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Pfizer Inc. Ye BD has served on advisory boards for AbbVie Korea, Celltrion, Daewoong Pharma, Ferring Korea, Janssen Korea, Pfizer Korea, Takeda, and Takeda Korea, has received research grants from Celltrion and Pfizer Korea, has received consulting fees from BMS Pharmaceutical Korea Ltd., Chong Kun Dang Pharm., CJ Red BIO, Curacle, Daewoong Pharma, IQVIA, Kangstem Biotech, Korea Otsuka Pharm, Korea United Pharm. Inc., Medtronic Korea, NanoEntek, ORGANOIDSCIENCES LTD., and Takeda, and has received speaker fees from AbbVie Korea, Celltrion, Cornerstones Health, Curacle, Daewoong Pharma, Ferring Korea, IQVIA, Janssen Korea, Pfizer Korea, Takeda, and Takeda Korea. Except for that, no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and the creation of the questionnaire: Song EM, Na SY, Hong SN, Ye BD. Writing-original draft: Song EM, Ye BD. Writing-review and editing: Na SY, Hong SN, Ng SC, Hisamatsu T. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Additional Contributions

The authors would like to thank all the doctors in Asia who participated in this web-based survey.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials are available at the Intestinal Research website (https://www.irjournal.org).

Supplementary Material

Detailed questions used in the current survey