Clinical presentation of COVID-19 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is recognized to have variable clinical manifestations. The clinical presentation of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) having COVID-19 is unclear.

Methods

We identified articles reporting about the clinical presentation of COVID-19 in those with underlying IBD from PubMed and Embase. The studies, irrespective of design or language, were included. The overall pooled frequency of various symptoms was estimated. Joanna Briggs Institute Critical appraisal checklist was used to assess the quality of studies.

Results

Eleven studies, including 1,325 patients, were included in the pooled analysis. The pooled estimates for clinical presentation were; fever: 67.53% (95% confidence interval [CI], 45.38–83.88), cough: 59.58% (95% CI, 45.01–72.63), diarrhea: 27.26% (95% CI, 19.51–36.69), running nose: 27% (95% CI, 15.26–43.19) and dyspnea: 25.29% (95% CI, 18.52–33.52). The pooled prevalence rates for abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting were 13.08% (95% CI, 9.24–18.19), 10.08% (95% CI, 5.84–16.85) and 8.80% (95% CI, 4.43–16.70) per 100 population, respectively.

Conclusions

The clinical presentation of COVID-19 in IBD patients is similar to the general population.

INTRODUCTION

Infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), leading to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), was declared officially as a pandemic by World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020 with reports of infection from most of the countries of the world [1]. The pandemic has changed the management practices as well as has brought challenges in providing care for the required once [2].

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is not untouched from this pandemic and has affected the care of these patients. Patients with IBD, both ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) could have an increased risk of COVID-19 infection in the light of use of various immunosuppressive and biologics. With increased risk of acquisition of COVID-19 in IBD patients, these patients can be asymptomatic or can present with typical symptoms of sore throat, fever, cough, dyspnea, sputum production, myalgia, fatigue, and headache [3]. Patients may also present with gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms including diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, loss of taste and smell [4,5]. The increased GI symptoms are thought to be angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) receptor mediated changes by the SARS-CoV-2 which is present throughout the gut mucosa in predominance [6]. In the absence of typical symptoms, it is difficult to differentiate these GI symptoms due to COVID-19 infection or due to disease flare.

Multiple studies have looked at the various GI and non-GI manifestations of COVID-19 infected general population however limited data is available about the clinical presentations of the COVID-19 infection in the IBD patients [7,8]. Therefore, we planned to do a systematic review of reports so far on the various clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 in patients with IBD, and to estimate the pooled prevalence of different clinical manifestations.

METHODS

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group guidance.

1. Database Search

We conducted an electronic databases search using PubMed and Embase on August 28, 2020. Keyword used for the search included “inflammatory bowel disease,” “ulcerative colitis,” “Crohn disease or Crohn’s disease” combined using operator ‘AND’ with “Coronavirus,” “COVID-19,” “SARS-COV-2,” “nCOV,” “coronaviridae infection” or “coronavirus disease 2019” (detailed strategy as described in Supplementary Table1). The eligible titles were combined and the duplicates were removed. After duplicate removal, the rest of the titles and abstracts were screened by 2 reviewers (A.K.S. and A.J.) for relevant studies. After screening of the titles and abstracts, relevant papers were selected for full text screening. Third reviewer (V.S.) was consulted for any differences and resolved after discussion. Bibliography of the included studies was also searched to find any relevant study.

2. Study Inclusion

We included all the relevant papers which reported the various presentations of COVID-19 in patients with IBD. Papers were included irrespective of the type of publication (original paper, abstract, letter, correspondence), format or language. We excluded studies which did not have relevant clinical data or the data was incomplete. We also excluded paper with data of < 5 patients with IBD.

3. Data Extraction, Comparisons, and Outcomes

Two reviewers (A.K.S. and A.J.) extracted the data from the included studies and any discrepancy was resolved by discussion with the third reviewer (V.S.). Extracted data included publication details (author and year), place of study, overall population of IBD patients and COVID-19 positive IBD patients, age, gender, disease type (CD or UC) and various GI and non-GI clinical presentations, i.e., diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, cough, sore throat, dyspnea, ageusia, anosmia, fatigue, myalgia, running nose. The basis of diagnosis of COVID-19 infection was also reported for the various studies (COVID19 RT-PCR [reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction] based diagnosis or clinical symptoms consistent with COVID-19 with radiological evidence of pneumonia). In case if the number of events were provided for the combination of 2 symptoms in a study, each symptom was given the same number of events. For each clinical manifestation the pooled prevalence was calculated for COVID-19 positive IBD patients. We also extracted the data for impact of various factors on clinical presentation including (1) pattern of underlying IBD (UC and CD), (2) underlying IBD as compared to overall population, (3) severity of COVID-19 in IBD patients, i.e., hospitalized and non-hospitalized cases.

4. Data Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using the meta package in R version 4.0.1 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). The prevalence was logit transformed. The pooled prevalence was computed using a random-effect method with inverse variance approach. Inverse variance approach with logit transformation was used as it performs well when the sample sizes of the included studies differ from each other. The prevalence was computed for 100 observations. The heterogeneity was assessed by I2 and P-value of heterogeneity (P < 0.10 was taken as statistical significance). We used a random-effect model irrespective of the I2 value.

5. Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias Assessment

Two of the investigators (A.K.S. and A.J.) independently assessed the methodological quality and risk of bias of every study. We used the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical appraisal checklist for studies reporting the incidence/prevalence [9]. Joanna Briggs Appraisal for incidence/prevalence data includes questions about the appropriateness of study sample and selection, description of setting and subjects, completeness of provided data and analysis, and the appropriateness of measuring the condition.

RESULTS

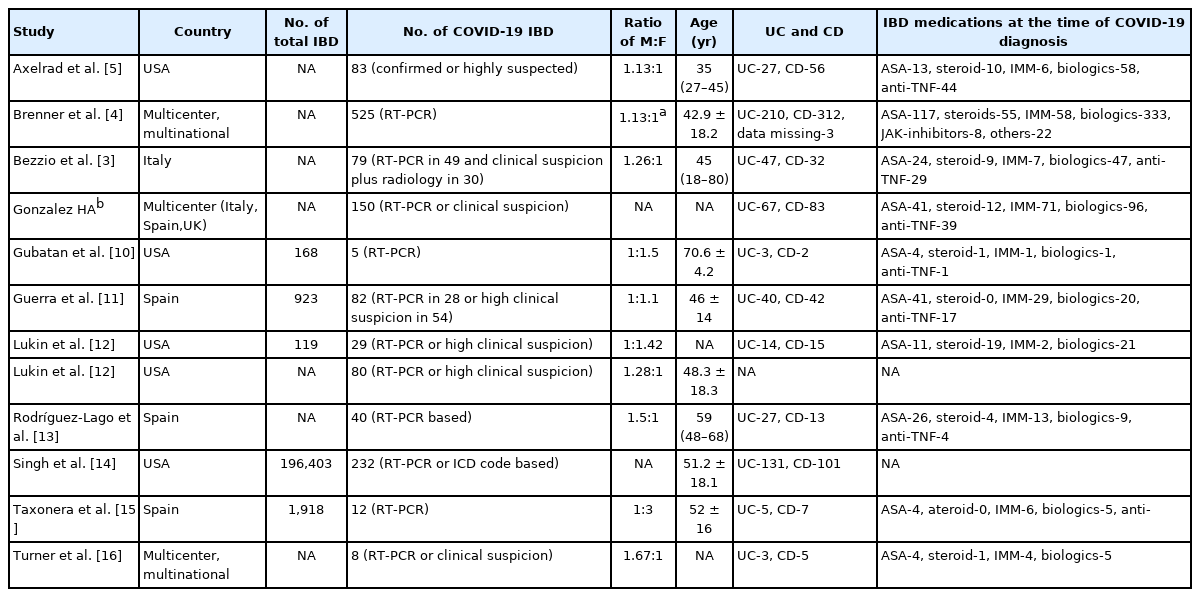

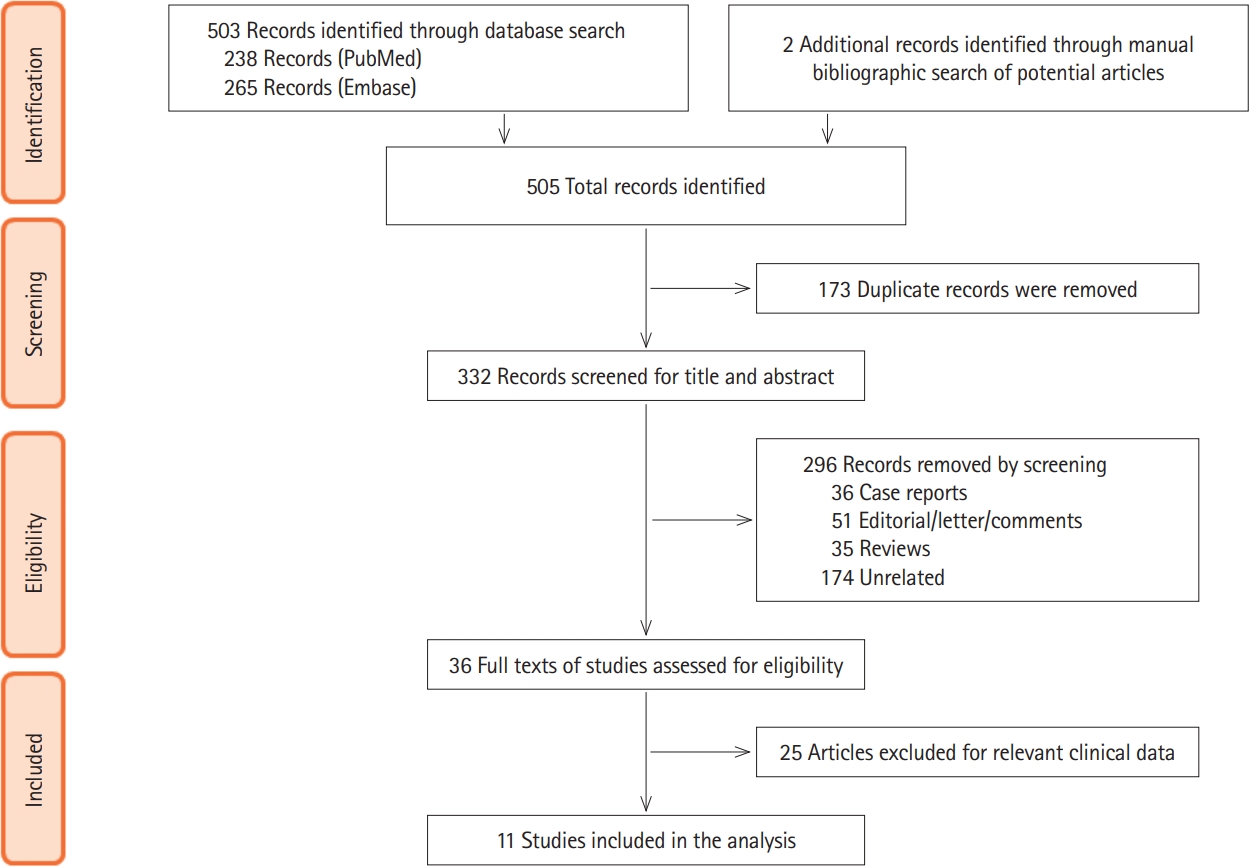

After the database search, a total of 503 titles were identified and 2 additional papers were identified from other sources. Total of 173 duplicates were excluded. A total of 332 articles were screened for the title and abstract and 36 papers underwent full text screening (Fig. 1, PRISMA flowchart). For final analysis, data from 11 studies was used for analysis. Table 1 provides the details of included studies including the place of study, overall population of IBD patients and COVID-19 positive IBD patients, basis of diagnosis, disease type (CD or UC) and clinical presentations [3-5,10-16].

PRISMA flowchart showing the process of screening and inclusion. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Eleven studies provided the data on symptoms of IBD patients with COVID-19 infections and included a total of 1,325 patients. They constituted 574 (43.3%) patients of UC and 668 (50.4%) of CD with data missing in 83 (6.26%).

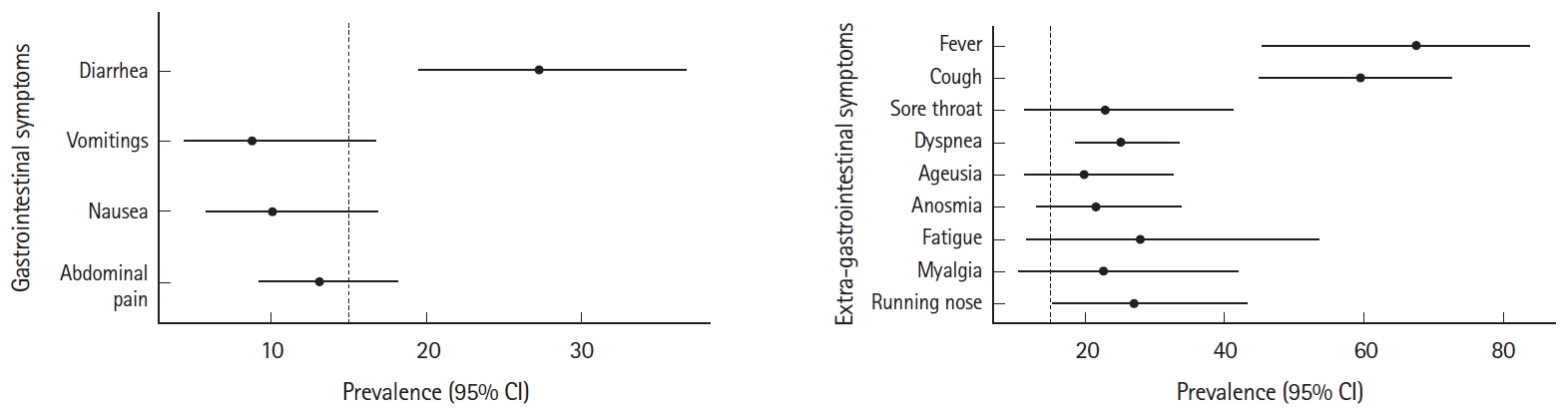

1. GI Symptoms in IBD with COVID-19

Out of the included 11 studies, 9 showed diarrhea as the commonest GI manifestation in IBD patients infected with COVID-19. The pooled prevalence rate of diarrhea in patients of IBD with COVID-19 was 27.26% (95% confidence interval [CI], 19.51–36.69; I2 = 87%) per 100 population. The pooled prevalence rates for abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting were 13.08% (95% CI, 9.24–18.19; I2 = 69%), 10.08% (95% CI, 5.84–16.85; I2 = 80%) and 8.80% (95% CI, 4.43–16.70; I2 = 85%) per 100 population, respectively (Fig. 2).

2. Extraintestinal Symptoms in IBD with COVID-19

Among the symptomatic patients, fever was the most common presentation in IBD patients with COVID-19 infection with a pooled prevalence of 67.53% (95% CI, 45.38–83.88; I2 = 96%) per 100 population. Other common manifestations were cough (59.58%; 95% CI, 45.01–72.63; I2 = 92%), running nose (27.00%; 95% CI, 15.26-43.16; I2 = 52%), dyspnea (25.29%; 95% CI, 18.52–33.52%; I2 = 76%), fatigue (27.96%; 95% CI, 11.57–53.52; I2 = 94%), myalgia (22.52%; 95% CI, 10.49–41.90; I2 = 91%), sore throat (22.93%; 95% CI, 11.21–41.21; I2 = 90%), anosmia (25.58%; 95% CI, 12.95–33.73; I2 = 84%), and ageusia (19.86%; 95% CI, 11.25–32.63; I2 = 85%) per 100 population, respectively (Fig. 3).

Pooled rates for extra-gastrointestinal symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in inflammatory bowel disease patients. (A) Fever, (B) cough, (C) sore throat, (D) dyspnea, (E) ageusia, (F) anosmia, (G) fatigue, (H) myalgia, and (I) running nose. IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval.

3. Impact of Various Factors on Clinical Presentation

Supplementary Tables 2-4 summarize the studies reporting impact (1) pattern of underlying IBD (UC or CD), (2) underlying IBD as compared to overall population (3) severity of COVID-19 in IBD patients, i.e., hospitalized and non-hospitalized cases on clinical presentation. The GI symptoms including diarrhea appeared to be more frequent in those with underlying IBD as compared to general population (Supplementary Table 3). Since none of these parameters were reported in more than 2 studies no pooled analysis was performed.

4. Risk of Bias

Risk of bias of included studies for prevalence of different presentations of COVID-19 infection in IBD patients and is given in Supplementary Table 5. Joanna Briggs guidance suggests against using a score for quality assessment we have not done the same.

DISCUSSION

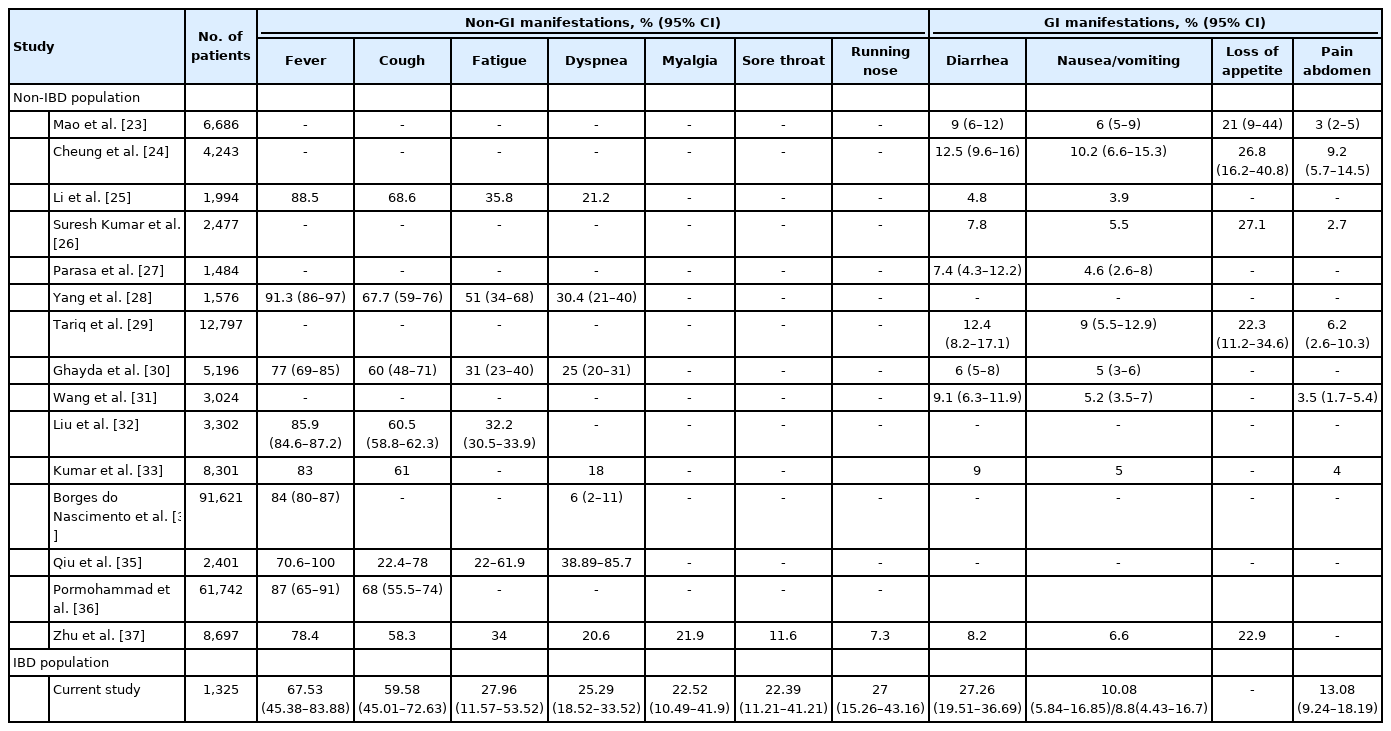

We found in the present meta-analysis that similar to the general population extraintestinal manifestations are the commonest presentation of COVID-19 infection in IBD patients with fever and cough being the commonest symptoms (Fig. 4). Furthermore, GI symptoms are also not uncommon in this group of patients with up to a quarter of the patients presenting with diarrhea which may sometimes be difficult to differentiate from the IBD flare in the absence of constitutional non-GI symptoms. Occasionally, patients may present with GI symptoms only or with paucity of other manifestations and could overlook these patients leading to serious consequences to the patients as well as to their contacts.

Summary plot of various clinical features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in inflammatory bowel disease. CI, confidence interval.

Initially thought to be a less common symptom, recent studies have shown an increasing number of patients presenting with diarrhea when infected with SARS-CoV-2 infection in the general population [17,18]. Recent meta-analysis has reported the pooled prevalence of GI symptoms in 18.6% of the COVID-19 patients with most common symptoms as anorexia (26.1%) preceded by diarrhea (13.5%), nausea (7.5%), vomiting (6.0%) and abdominal pain (5.7%) [19]. Other studies have reported lower prevalence of diarrhea (7%–10%) in the general population infected with COVID-19 [20,21]. GI symptoms when present are also found to correlate with severe COVID-19 infection and intensive care unit admission in the general population. It seems, although there are no direct comparisons, that frequency of diarrhea in IBD patients may be more than in the general population.

Though GI symptoms are increasingly studied in the general population, limited data is available in the IBD population infected with COVID-19 with increased prevalence of diarrhea and other GI symptoms [22]. This increased prevalence of diarrhea in IBD patients may be related to the worsening of underlying disease due to SARS-CoV-2. Evidence shows that SARS-CoV-2 has gut tropism and initiates an inflammatory response in the gut and causes elevated fecal calprotectin levels and systematic interleukin-6 response in patients with diarrhea compared to patients without diarrhea [6]. Fecal calprotectin may be elevated in diarrhea in COVID-19 patients even in the absence of IBD [6]. Therefore elevated calprotectin may not always indicate flare and COVID-19 should be ruled out in current pandemic situation. Our analysis also demonstrates that the GI manifestations especially diarrhea may be more frequent in patients with underlying IBD as compared to general population as reported in previous meta-analysis (Table 2) [23-37].

Comparison of the Prevalence of Various COVID-19 Symptoms in General Population vis-à-vis Those with Underlying IBD

Another notable finding in our meta-analysis was the predominance of abdominal pain in IBD patients which is uncommon in the general population infected with COVID-19 as shown in other studies [19]. Exact mechanism of abdominal pain is not known. The pain can be attributed to the underlying worsening of inflammatory status of IBD or could be unrelated to underlying IBD as shown in the recent paper where underlying pancreatic injury could go unnoticed [38].

ACE2 receptor is a critical cell receptor for SARS-CoV-2 to invade the host cells. Apart from lungs, ACE2 receptors expression has been demonstrated in the intestinal tract. Binding of SARS-CoV-2 to these ACE2 receptors in the intestinal tract has been proposed as an alternative pathway of acquiring the coronavirus infection by directly invading the gut barrier [39]. After SARS-CoV-2 infection, the interaction between intestinal microbiota and pro-inflammatory cytokines may also lead to the injury of the GI tract and causing different GI manifestations. SARS-CoV-2 virus had been detected in the feces of 53.4% of patients with COVID-19 infection [40]. However, whether the viral RNA detected in fecal samples correlates with GI symptoms or infectious viral particles is unclear for IBD as well as non-IBD patients.

In the light of limited data on the GI manifestations of COVID-19 in IBD patients, this paper provides important clinical data on the cumulative frequency of various GI symptoms in COVID-19 infected IBD patients along with the more common extra-gastrointestinal manifestations. With the potential of new surges in various locations, the results of our meta-analysis could guide clinicians and patients regarding the possible manifestations of COVID-19 in IBD and should be evaluated cautiously not to be mistaken for simple flare of underlying disease. The findings of our meta-analysis also show high prevalence of few symptoms including abdominal pain in IBD patients compared to non-IBD COVID-19 or non-COVID-19 IBD flare patients and could be a potential research question for pathogenesis of COVID-19 in IBD patients.

The meta-analysis has its limitations, firstly with the limited number of studies reporting on IBD with COVID-19. Secondly, most of the studies have not looked at the GI symptoms in prospective manner and could lead to the recall bias for milder symptoms, similarly the severely ill patients e.g. on mechanical ventilation could lead to reporting bias for not being able to report the symptoms like abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. The fact that most of the studies were not primarily addressed to report the clinical presentation of COVID-19 in IBD. The studies reporting the clinical presentation as per the underlying IBD subtype were limited (only 2) and therefore a formal comparison could not be done. Similarly, the association of symptoms with underlying severity of COVID-19 IBD was also reported only in 2 studies. Most of the studies have also not reported the baseline status of the underlying disease and symptoms prior to acquiring COVID-19 which could lead to overestimation of GI symptoms in such cases. The other possible causes for in hospital diarrhea including antibiotics or drug associated diarrhea have also not been adequately evaluated in most of these studies. A possibility that there may be duplication of data (since SECURE IBD is a multinational registry) cannot be ruled out but we excluded studies that reported that their data is included in SECURE IBD.

In conclusion, COVID-19 in patients with IBD has a presentation similar to the general population but diarrhea could occur in a quarter of patients. Other GI manifestations in these patients include abdominal pain, vomiting and nausea. It also appears that GI manifestations especially diarrhea may be more common as compared to general population.

Notes

Funding Source

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: Sharma V. Data curation: Singh AK, Jena A, Jha DK. Formal analysis: Kumar-M P. Methodology: Singh AK. Supervision: Sharma V. Validation: Sharma V. Writing - original draft: Singh AK, Jena A, Kumar-M P, Jha DK. Writing - review & editing: Sharma V. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials are available at the Intestinal Research website (https://www.irjournal.org).

Supplementary Table 1. Detailed Search Strategy for the Systematic Review

ir-2020-00108-suppl1.pdfSupplementary Table 2. Studies Reporting the Clinical Presentation in UC and CD Separately

ir-2020-00108-suppl2.pdfSupplementary Table 3. Studies Reporting the Clinical Presentation in COVID-19 Patients with Underlying IBD and in General Population

ir-2020-00108-suppl3.pdfSupplementary Table 4. Studies Reporting the Clinical Presentation in COVID-19 IBD Patients with Regard to Severity (Hospitalized vs. Non-hospitalized)

ir-2020-00108-suppl4.pdfSupplementary Table 5. Risk of Bias Estimation Using Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for the Incidence/Prevalence Data Reporting Clinical Symptoms of Risk of COVID-19 Infection in IBD Patients

ir-2020-00108-suppl5.pdf