Association of Gallbladder Polyp with the Risk of Colorectal Adenoma

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Gallbladder polyps and colorectal adenomas share many common risk factors; however, their association has never been studied. The aim of this study was to investigate this association in asymptomatic healthy subjects.

Methods

Consecutive asymptomatic subjects who underwent both screening colonoscopy and abdominal ultrasonography at Kyung Hee University Hospital in Gang Dong between July 2010 and April 2011 were prospectively enrolled. The prevalence of colorectal adenoma was compared between subjects with or without gallbladder polyps. Furthermore, a logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the independent risk factors for colorectal adenoma in these subjects.

Results

Of the 581 participants, 55 presented with gallbladder polyps and 526 did not have gallbladder polyps. Participants with gallbladder polyps showed a trend toward a higher prevalence of colorectal adenoma than those without gallbladder polyps (52.7% vs. 39.2%, P=0.051). Although the result was not statistically significant, gallbladder polyps were found to be a possible risk factor for colorectal adenoma (odds ratio=1.796, 95% confidence interval=0.986-3.269, P=0.055), even after adjusting for potential confounding factors. There was no difference observed in colorectal adenoma characteristics between the two groups.

Conclusions

Our results suggest a possible association between gallbladder polyps and colorectal adenomas. Future studies with larger cohorts are warranted to further investigate this matter.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a significant public health problem as its incidence and mortality have continuously increased in the world.1 Since CRC develops to carcinoma from adenoma in most cases, early detection and removal of colorectal adenoma may decrease CRC-related mortality.2-4 Therefore, identification of risk factors associated with colorectal adenomas may facilitate screening and prevention of CRCs.

Gallbladder (GB) polyps are frequently diagnosed on routine abdominal ultrasonography; however, their clinical significance is unclear in most cases. The risk of GB polyps has been linked to obesity,5 glucose intolerance,6 metabolic syndrome,7 and an increased BMI,8 which are also common risk factors for colorectal adenoma.9-11 Further to these observations, we hypothesize that there exists an association between GB polyps and colorectal adenomas. To our knowledge, such an association has not been investigated to date.

In the present prospective study, we evaluated the association between GB polyps and colorectal adenomas in healthy subjects who were considered representative of the general population.

METHODS

1. Study Participants

Consecutive asymptomatic individuals who underwent both screening colonoscopy and abdominal ultrasonography as part of their medical checkup between July 2010 and April 2011 at the Health Promotion Center of Kyung Hee University Hospital in Gang Dong, Seoul, Korea were recruited. In Korea, healthy individuals undergo medical screening programs for early detection of diseases. Participants in our program undergo a variety of examinations including a physical examination, chest radiography, electrocardiography, blood laboratory tests, urine analysis, abdominal ultrasonography, upper endoscopy, and colonoscopy. Exclusion criteria in the present study were age <30 or ≥75 years, incomplete colonoscopy due to poor bowel preparation or failure to achieve cecal intubation, personal history of colonic neoplasia or inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal surgery or cholecystectomy, polyposis syndromes or hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, poor general condition of worse than American Society of Anesthesiologists grade III, symptoms or signs indicating the need for a colonoscopy (such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, anal bleeding, or positive results on a fecal occult blood test), and inability to provide informed consent. To avoid potential interfering effects of medications, individuals who had been regularly taking NSAIDs, aspirins, or statins for more than 1 year were also excluded from the analysis.

2. Definitions and Exposure Measurements

All participants were interviewed by well-trained nurses regarding their smoking habits; diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypertension status; family history of CRC in first-degree relatives; history of regular use of aspirins, NSAIDs, or statins; and history of colorectal surgery or cholecystectomy. Current smoking was defined as the usage of at least one pack per week for more than 12 months. Regular use of medications was defined as taking such medications for more than 12 months. Hypertension was defined as a blood pressure of ≥140 mmHg or the use of anti-hypertension medication. DM was defined as a fasting glucose level of ≥126 mg/dL or the use of insulin or hypoglycemic agents. Height and body weight, used to calculate BMI, were measured by trained nurses. Informed consent was obtained from each participant. The present study was conducted according to the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gang Dong (KHNMC IRB 2010-053).

3. Colonoscopy and Abdominal Ultrasonography

All participants underwent dietary restriction for 3 days and a bowel preparation process by drinking 4 L of polyethylene glycol solution during the 12 hours prior to colonoscopy until clear rectal fluid was evacuated. Signs and symptoms of potential complications of colonoscopy were explained to each participant, and all participants provided verbal and written consent prior to the procedure. For conscious sedative colonoscopy, an individualized dose of midazolam and/or propofol was administered to each patient by a gastroenterologist according to his/her age, weight, and general condition. An antispasmodic (10 mg hyoscine methobromide, intravenously) was administered to participants with no contraindications for the drug. All colonoscopic examinations were performed by experienced gastroenterologists using a standard video colonoscope (EC-590ZW/L, Fujinon Inc., Saitama, Japan), by following a standardized protocol. All detected colorectal polyps were biopsied or polypectomized for histopathologic examination, except for multiple polyps in the rectosigmoid area that appeared to be hyperplastic polyps based on endoscopic features consistent with a hyperplastic histology such as small size, sessile shape, pale color, and a type 1 or 2 pit pattern.12 In addition, all polyps were photographed, and their characteristics such as size, number, and location were documented. The size of each polyp was estimated by comparing it with open biopsy forceps (Olympus FB-28U-1, Aomori Olympus Co., Ltd., Aomori, Japan); forceps of a larger size were used for multiple polyps. The proximal colon was defined as the colonic region from the cecum to the splenic flexure, and the distal colon, as the colonic region distal to the splenic flexure. Polyps were classified as single or multiple (≥2). All polyps, pathologically evaluated by two gastrointestinal pathologists, were classified in accordance with the World Health Organization criteria.13 A colorectal adenoma was defined as one in the colon and rectum regardless of its grade or villous component. An advanced adenoma was defined as one with a diameter of ≥10 mm, an adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, or an adenoma with villous features in >25% of its area.

Abdominal ultrasonography after fasting was performed by two certified radiologists as a routine screening procedure using one of three ultrasound units (iU22 xMATRIX, Philips Electronics Ltd., Amsterdam, the Netherlands). The liver, GB, bile duct, pancreas, spleen, and kidneys were routinely examined. The diagnostic criterion for GB polyps was a hyperechoic immobile echo protruding from the GB wall into the lumen without an acoustic shadow, regardless of its histology. The radiologists and colonoscopists were blinded to the results of the examinations of the other group.

4. Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint was the prevalence of colorectal adenoma according to GB polyp status. Secondary outcomes included characteristics of detected lesions (number, multiplicity, location, and size) in both groups, with or without GB polyps. All data are presented as mean±SD for continuous variables and as number (percentage) of participants for categorical variables. For intergroup comparisons, continuous variables were analyzed using the Student's t test and categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Logistic regression analysis was performed to control for confounding variables and to identify independent risk factors for colorectal adenoma. Statistical adjustments were applied for potentially relevant variables that differed between the two groups in univariate analysis with a P value of <0.1. We computed the OR and 95% CI using logistic regression analysis. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant, and a P value of <0.1 was considered indicative of a statistical trend. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 13.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

During the study period, 813 subjects underwent screening colonoscopy and abdominal ultrasonography at the same medical check-up and answered the questionnaire at the time of the initial colonoscopy. We excluded 232 subjects for one or more of the following reasons: age <30 years or ≥75 years (n=14); a general condition worse than American Society of Anesthesiologists grade III (n=6); symptoms or signs indicating the need for colonoscopy (n=2); personal history of colorectal polyps (n=97); colorectal surgery (n=5) or cholecystectomy (n=14); incomplete colonoscopy due to poor bowel preparation (n=16); regular use of NSAIDs, aspirins, or statins (n=71); and/or the inability to provide informed consent (n=7).

The remaining 581 participants were comprised of 354 (60.9%) men and 227 (39.1%) women, and the mean subject age was 47.1±9.2 years. The overall prevalence of colorectal adenomas was 40.4% (235/581), and that of GB polyps was 9.5% (55/581). Subjects with GB polyps showed a trend toward a higher prevalence of colorectal adenoma than those without GB polyps (52.7% vs. 39.2%, P=0.051).

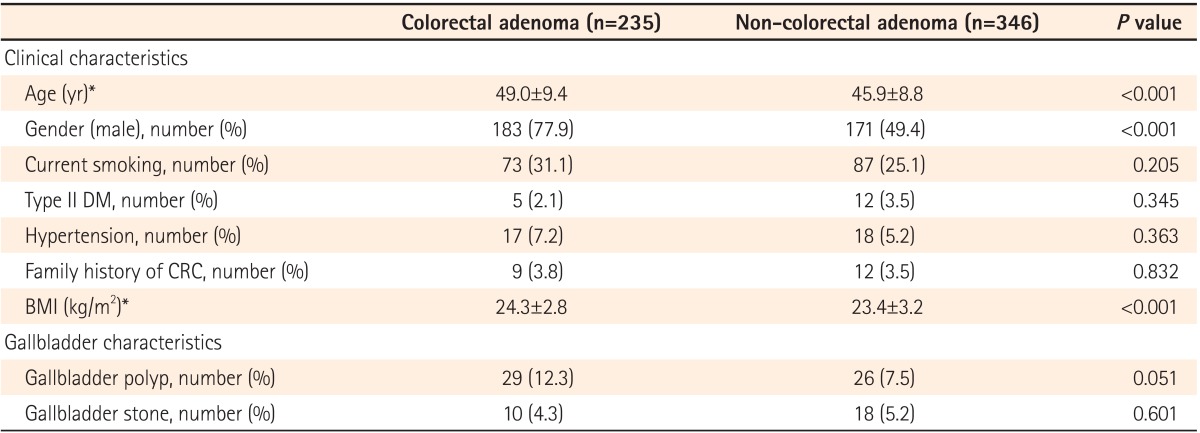

1. Clinical and GB Characteristics according to Colorectal Adenoma Status

As expected, participants of old age, male gender, and a high BMI were more likely to be in the colorectal adenoma group than the non-colorectal adenoma group (Table 1). Furthermore, those with colorectal adenomas tended to showed a trend toward a higher prevalence of GB polyps than those without colorectal adenomas (12.3% vs. 7.5%, P=0.051). However, there was no statistically significant difference in any other clinical or GB characteristics between the two groups.

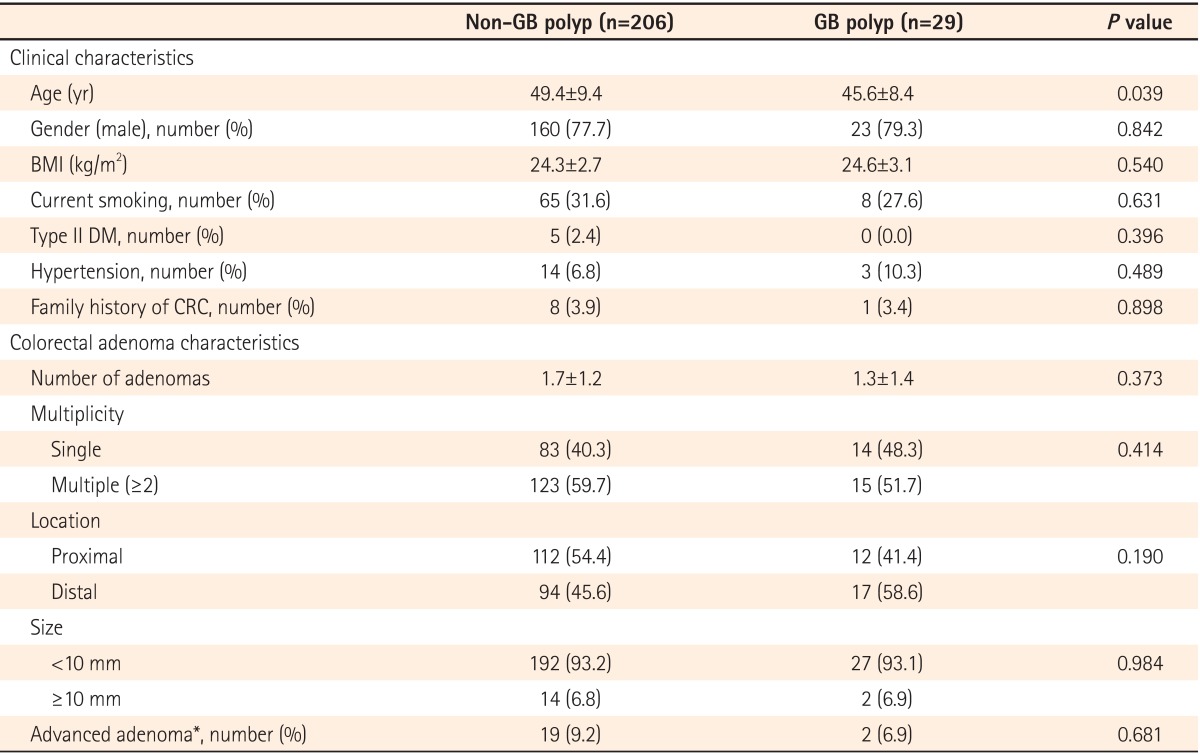

2. Comparative Analysis of GB Polyp and Non-GB Polyp Groups among Patients with Colorectal Adenoma

The clinical and pathologic characteristics of the participants with colorectal adenoma according to the presence of GB polyps are described in Table 2. Participants with colorectal adenoma in the non-GB polyp group were older than those in the GB polyp group (P=0.039). There was no statistically significant difference in any other clinical characteristics between the two groups. Furthermore, the groups did not differ in characteristics of the detected colorectal adenoma either.

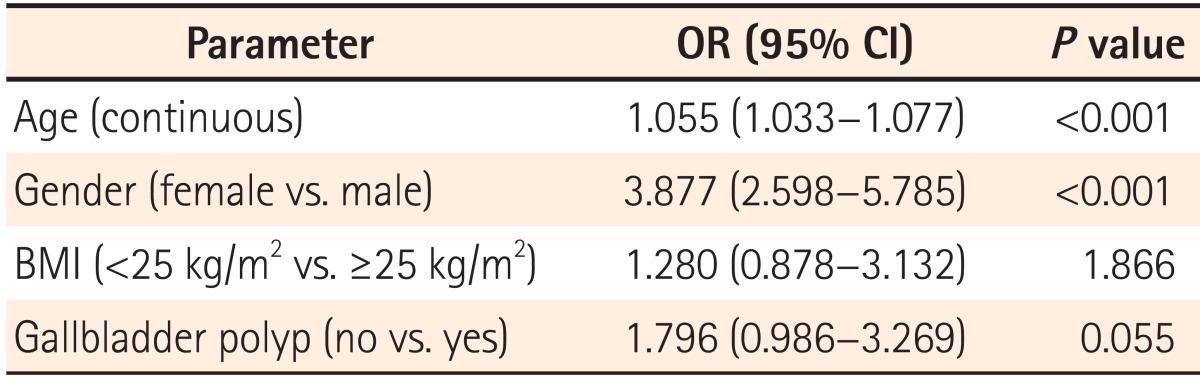

3. Risk Factors for Colorectal Adenoma

To determine independent predictors of colorectal adenoma, we performed logistic regression analysis after adjusting for age, gender, BMI, and GB polyp status, which were potentially relevant variables that differed between the two groups in univariate analysis with a P value of <0.1 (Table 3). In this analysis, age and gender, which are well-known risk factors for colorectal adenoma, were found to be independent risk factors of colorectal adenoma. However, GB polyps as a risk factor for colorectal adenoma only showed a statistical trend (OR=1.796, 95% CI=0.986-3.269, P=0.055).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the present analysis is the first prospective study to evaluate the possible association between GB polyps and colorectal adenomas in healthy individuals. In this study, participants with GB polyps showed a trend toward a higher prevalence of colorectal adenomas than those without GB polyps (P=0.051). In addition, GB polyps as a risk factor for colorectal adenoma only exhibited a statistical trend, even after adjusting for multiple possible confounding factors in multivariate analysis (P=0.055).

Although little is known about the association between GB polyps and colorectal adenomas, the two conditions have many common risk factors, suggesting a possible linkage.5-11 Segawa et al.5 suggested that obesity contributed to the development of GB polyps on analysis of 21,771 individuals. Chen et al.6 studied 3,647 Chinese individuals and reported that glucose intolerance might influence the risk for GB polyps with a 1.51-fold increased risk (OR 1.506, P<0.05). More recently, Lim et al. reported a nearly 2.35-fold increased risk (OR 2.35, 95% CI=1.53-3.60) of GB polyps in participants with metabolic syndrome and a 1.64-fold increased risk (OR 1.64, 95% CI=1.19-2.26) in those with insulin resistance, in a multivariate analysis of 1,523 subjects.7 Increased BMI has also been reported to be related to the prevalence of GB polyps.8 In the literature, the risk factors for GB polyps such as obesity, glucose intolerance, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and increased BMI have also been suggested as risks for colorectal adenomas.9-11 Therefore, the possible association between GB polyp and colorectal adenoma may result from exposure to the same risk factors, and the development of both conditions may be the consequence of the same pathway involved in such exposure. However, the possible association between these two conditions should be further investigated in larger studies, as our results only demonstrated statistical trends.

In our study, the prevalence of colorectal adenoma was 52.7% among participants with GB polyps and 39.2% among those without GB polyps. A sample size of approximately 198 cases and 198 controls is required to achieve power of 80% with a confidence level of 5% (UCSF biostatistics, www.epibiostat.ucsf.edu/biostat/sampsize.html). However, we only enrolled a total of 581 individuals, and among these, only 55 had GB polyps, as we can't determine the correct sample size because of a lack of extant data on this topic. Therefore, we consider this a pilot study to determine a possible association between GB polyps and colorectal adenomas. Another limitation of our study is that we were not able to confirm the histology of the GB polyps as our data were obtained from asymptomatic individuals who underwent ultrasonography only as part of health examinations. Nevertheless, the asymptomatic nature of GB polyps may prevent histological confirmation, and ultrasonography is the gold standard diagnostic tool for GB polyp detection.

Despite these limitations, our study yielded interesting findings for various reasons. First, this is the first prospective study to evaluate the possible association between GB polyps and colorectal adenomas in healthy individuals. With the widespread use of abdominal ultrasonography in medical check-ups, the possible association of GB polyps with colorectal adenomas should be considered in patients with GB polyps. Our study may inspire further investigation on the issue. Second, our study population was likely representative of the general population, because apparently healthy individuals were prospectively enrolled with strict exclusion criteria. In addition, our reported prevalence of colorectal adenomas and GB polyps was similar to what is expected, indicating a minimal selection bias. The overall prevalence of colorectal adenomas in our study (40.4%) was higher than that of healthy individuals who underwent colonoscopic screening for colorectal neoplasia (31-32%).10,14 The prevalence of GB polyps in our study (9.5%) was similar to that reported in a population-based study of 43,606 cases in Korea8 and a prospective study of 34,669 individuals in China (8.5-9.5%).15 Finally, we adjusted for multiple possible confounders for colorectal adenoma and GB polyps in our analysis, and collected high quality data as all measurements and questionnaires were completed by trained nurses.

In summary, individuals with GB polyps showed a statistical trend toward a higher prevalence of colorectal adenomas than those without GB polyps and GB polyps showed a statistical tendency to be a possible risk factor of colorectal adenoma. Therefore, further studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to confirm this possible association between GB polyps and colorectal adenomas with statistical significance.

Notes

Financial support: This research was supported by the Research Fund from JEIL Pharm. CO., LTD. in 2010.

Conflict of interest: None.